It’s already bigger than you think.

Amazon seems to treat Amazon Music like it does Prime Video: a good service on its own, but a killer one as part of a Prime subscription.

In the last couple of weeks, a lot of people have found themselves Googling things like “best music service not Spotify.” Things like #deletespotify have trended repeatedly. All of Spotify’s competitors should send Joe Rogan a gift basket, really. But if users do leave Spotify, where will they go?

It’s easy to see streaming as a two-horse race. There’s Spotify and there’s Apple Music. And then, way down below, there’s Tidal and Deezer and Pandora and SoundCloud and YouTube Music and SiriusXM and countless others.

But Amazon might be the company to watch in the audio wars. For starters, it’s already bigger than you think:

Amazon has a big advantage here: It doesn’t really need to make money from audio. As Spotify and others are finding, the economics of the audio business are rough and not getting easier. But Amazon seems to treat Amazon Music like it does Prime Video: a good service on its own, but a killer one as part of a Prime subscription.

Audio suits a lot of Amazon’s needs, actually:

And then there’s Audible. Audible is a wholly separate thing from Amazon Music, which obviously started with audiobooks but more recently has added podcasts to the platform and funded its own “Audible Originals,” which are just, well, podcasts. It wouldn’t take much to combine Audible with Music, and maybe even Prime Video, for a pretty powerful media subscription.

The big question here: Is audio a business or a feature? Spotify, Clubhouse and others are betting it’s a business. Apple’s betting it’s a feature, better off rolled into something like an Apple One subscription, more of a marketing engine than a profitable enterprise on its own. And Amazon’s clearly in the feature camp as well: Music can bring people into its other services, get people inside of Amazon’s universe and put its tools a click or voice command away anytime you have headphones on.

Streaming execs have always told me that people don’t really switch music services. Your service gets to know you, the recommendations get better, you understand the interface, you build a library and the switching costs get too high given that it’s all the same music everywhere you go. (I’ve been on Spotify for a decade for this exact reason.) That’s why moments like the Rogan controversy matter so much: They make people shop again. And Amazon’s surely hoping millions of Prime subscribers discover they already have access to a pretty good music service.

A version of this story also appeared in today’s Source Code; subscribe here.

Understand how new technologies like AR and VR, gaming, streaming and Web3 are coming together to form the metaverse. Every Tuesday, Thursday and Friday.

Your information will be used in accordance with our Privacy Policy

Thank you for signing up. Please check your inbox to verify your email.

Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again.

A login link has been emailed to you - please check your inbox.

David Pierce ( @pierce) is Protocol’s former editorial director. Prior to joining Protocol, he was a columnist at The Wall Street Journal, a senior writer with Wired, and deputy editor at The Verge. He owns all the phones.

Meet the startup where CEOs and entrepreneurs video chat to get in the flow.

Flow Club is a study hall for adults that costs $400 a year.

Lizzy Lawrence ( @LizzyLaw_) is a reporter at Protocol, covering tools and productivity in the workplace. She’s a recent graduate of the University of Michigan, where she studied sociology and international studies. She served as editor in chief of The Michigan Daily, her school’s independent newspaper. She’s based in D.C., and can be reached at [email protected].

Work-from-home distraction is inevitable. But what if you had a group of strangers holding you accountable over video?

This is the central idea behind Flow Club, a virtual coworking startup that launched last week. Co-founder Ricky Yean likes to think of it as a workout class or the “Peloton for coworking,” but instead of training your body, you’re training your mind. Yean and co-founder David Tran — who have embarked on two previous startups together — used Zoom to cowork throughout the pandemic. Very quickly, they realized how effective virtual coworking could be.

“We’re building a space that you can go for yourself,” Yean said. “We think that, ultimately, it enhances your ability to work better, but also just your wellness overall and how you feel.”

Coworking outside of the traditional office environment isn’t new; it’s why concepts like WeWork were so popular. Remote coworking is prominent too, whether you’re interacting with real people via Discord server or with your favorite influencer via a “study with me” video. Using internet strangers for motivation is helpful, especially when many of us are still isolated at home. Yean and Tran aren’t the only ones capitalizing on the virtual coworking trend; British startup Flown, which also markets itself as the “Peloton for work,” launched early on in the pandemic.

Flow Club offers a two-week trial (or four-week, if you’ve been referred), after which it charges $40 per month or $400 per year for an unlimited number of sessions. There are around 200 sessions throughout the week. It’s a steep price, and might not be worth it for people who are comfortable organizing ragtag work groups themselves. Productivity expert Rahul Chowdhury said he prefers working alone, so Flow Club doesn’t entice him. But he can see why people would pay to work with a group of “laser-focused” strangers.

“If the groups help you get stuff done when you’re unable to focus on your own and earn back multiples of your investment, it can be worth the price,” Chowdhury told Protocol.

I joined my first Flow Club session last week, greeted by a row of random faces and easygoing jazz music. My host, Irene Yu, prompted me to go to the Flow Club website to write down a few tasks I wanted to complete. She explained that the tasks would then float over my video screen for all participants to see. One Flow Clubber wanted to achieve inbox zero. Another wanted to walk their dog.

We spent the first five minutes sharing our goals for the session, with as much or as little detail as we wanted. Yu presented us with a trivia question: What is the tallest breed of dog? (Great Danes, if you’re curious). Each host has their own preferred icebreaker, Yu told me. Yean started the trend by telling dad jokes to kick off his own Flow Club sessions.

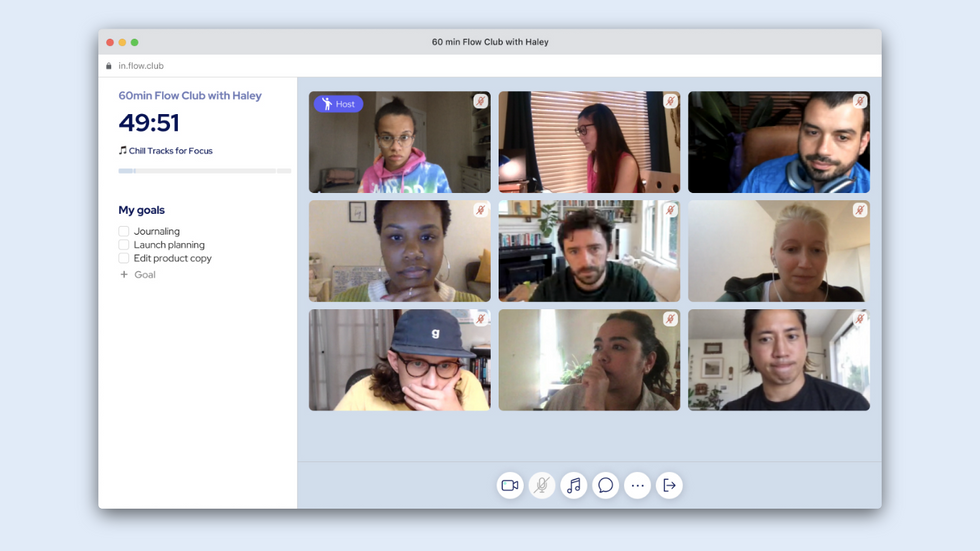

Flow Club’s deep focus session.Image: Flow Club

Flow Club’s deep focus session.Image: Flow Club

Sessions can be 60, 90 or 120 minutes long. After the five-minute share out, people mute themselves and go into work mode. You can turn your camera off if you want, but Flow Clubbers often leave them on for maximum accountability. I decided to leave mine on and, surprisingly, I forgot about it after a little while. Hosts choose background music that you can leave on or turn off. At the end of the session, a gong goes off and participants come together to share how much progress they made.

“One of the questions that some hosts like to ask is: Were you surprised by the gong at the end?” Yean said. “If it shook you, it means that you got lost. It’s a nice feeling to know that you got lost in the work.”

Sharing your video and work habits with a bunch of random people might not sound appealing — especially in the context of Zoom fatigue, a phenomenon we are all-too-familiar with at this stage of the pandemic. It’s a common pushback, so the Flow Club team has worked to make the product feel less like a Zoom meeting. The interactions during a session are minimal, and the video boxes are small. Flow Club isn’t for socializing. LIke working in a library or café, it’s meant to put you in the presence of strangers who are also doing work.

“The videos are really just there for accountability purposes,” Yean said. “If you were to use this platform to really talk, it wouldn’t be optimal, because you wouldn’t be able to see each other’s faces that clearly.”

Still, Flow Club’s early users have found social advantages as well. Flow Club is most useful for people who work independently, and sometimes those people are looking for others to bounce ideas off of. Yu started using the service in March of last year after quitting her Amazon job. She had just started her own company, Skiplevel, to help professionals become more technical without learning how to code. “I was kind of struggling, not having a team and working on my company, just me,” Yu said.

Yu found Flow Club improved her work ethic, and as she kept going back, she found herself making friends. It helped her business, as some fellow participants became clients. The networking doesn’t happen “consciously” during the session, Yu said. It happens when people read her bio and decide to follow up with her after. “I always like to say people come for the productivity and stay for the community,” Yu said.

Yean wouldn’t give me an exact number, but said Flow Club has several hundred users spanning more than 25 countries. Some companies, like Animalz, Baydin and Hustle Fund, reimburse subscriptions for their employees so co-workers can sign up for sessions together. Others, like Yu, are solopreneurs or choose to come for their own personal productivity. Tasks are big or small, and can range from “boil an egg” to “figure out acquisition strategy.”

“Some of these people could be power players, big CEOs, founders; others are just people like you and me,” Yean said. “They’re doing the same thing. They’re all like, ‘I have to respond to these emails.’”

Not all users are in tech. Julie Alexander, a business professor at Miami University in Ohio, describes Flow Club as “adult study hall.” She’ll block out two to four sessions a week for grading and lesson prepping. Alexander was diagnosed with ADHD as an adult, and found herself struggling to stay focused throughout the day. She came across Flow Club a few months ago while Googling solutions for people with ADHD. One solution is “body doubling”: completing tasks alongside other people.

“I actually haven’t taken my Adderall since I started using Flow Club,” Alexander said. “Which is kind of amazing, though I’m sure it’s not typical.”

Antonio Puente, an assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University’s medical school, said most ADHD patients would still require medication while participating in Flow Club. But he said he sees the merit in a program like Flow Club for people with ADHD. Behavioral programs often work in tandem with medication to help people with ADHD concentrate on tasks. “It’s not rocket science, the management of it,” Puente said. “But the hard part, especially when it comes to ADHD, is consistency. Having that structure can really help.”

Another potential benefit of services like Flow Club, Puente pointed out, is normalizing the use of outside programs to help people with ADHD in the workplace. While it’s easy for Puente to write accommodations for students, it’s difficult to do the same with employees.

“How do you get extended time on various work assignments? How can you help the employee concentrate better?” Puente said. “The classroom is a lot more set up for accommodations, but there aren’t these external structures that are easily implemented from a career standpoint.”

Work is in flux and more flexible than ever. The idea of meeting up with strangers over silent video chat to get “in flow” might have sounded ridiculous before March 2020. But in the chaos of today’s workplace, where people can work from RVs or in a video game office if they want to, maybe a serene work session with strangers is what we need.

Lizzy Lawrence ( @LizzyLaw_) is a reporter at Protocol, covering tools and productivity in the workplace. She’s a recent graduate of the University of Michigan, where she studied sociology and international studies. She served as editor in chief of The Michigan Daily, her school’s independent newspaper. She’s based in D.C., and can be reached at [email protected].

The last two years have seen more change than the prior 20, but change will keep coming, quickly. In this third of three articles, we look at how to keep on top of the changing work world.

Chris Stokel-Walker is a freelance technology and culture journalist and author of “YouTubers: How YouTube Shook Up TV and Created a New Generation of Stars.” His work has been published in The New York Times, The Guardian and Wired.

This is part three of a three-part series exploring the experience of frontline workers and new workplace tools being deployed to support them.

Changes born out of a crisis have upended every single workplace in the last two years. The old rulebook has been torn up, and new rules were written about how to communicate with and keep employees happy. Investing in effective communications technology has become core to that new world of work.

Three in four frontline workers believe good technology that keeps them in touch with their higher-ups is a must-have for any good business. And in turn, managers are recognizing the need for change. 94% feel they have to prioritize upgrading and changing their frontline technology to stay up to speed with the rapidly changing workplace.

“Are you offering them the ability to provide their feedback, and their input, and be a part of the products or solutions that you’re building? Will you recognize them?”

It’s a concern that’s well-known to many. Workplace, a business communication tool from Meta, recently commissioned research to try to understand the changing relationship between frontline staff and their back-office bosses. “What we’ve found is that there’s a critical gap in communications [that] frontline workers, and particularly frontline managers, waste on average 387 hours a year,” said Abby Guthkelch, Head of Global Executive Solutions at Workplace. “That’s equivalent to 9.3 working weeks on this disconnect, this lack of ability to get in touch with and connected with head office.”

Workplace Tech - The Future of the Frontline youtu.be

Tackling that gap is something organizations need to do now to stay competitive and not fall behind.

Four in five managers feel frontline employees’ experiences are shaped by how good their interaction with technology is. And that number is likely to increase as tech is woven further into the workplace, keeping us all connected. Half of U.S. workers would leave their job if the frustration of getting their workplace technology to work got too difficult, according to Workfront. One-third of workers already have.

That’s bad news for some businesses, but good news for those that are preparing to future-proof themselves, and offering the technology and support that frontline workers crave so much after the last two years of stresses and strains in their place of work. “It’s a really poignant question right now: how to attract talent,” said Christine Trodella, head of Workplace from Meta. “It’s one of the biggest challenges that all companies and all industries are facing. We’ve seen a real dramatic shift in the values of the employee population as those demographics change.”

That means clear lines of communication, enabled by the clever use of technology. It also means deploying tech at certain moments to improve performance at work — a survey by Meta found that 53% of frontline workers believed technology that could monitor things like sales goals and that customer service ratings could help improve their performance at work, making them more productive and enabling them to feel better about the difference they’re making to their business.

It’s all brokered by technology, which is why investing in and bringing to bear the best use of such tech is a crucial component of building the business of the future. “Are you offering the flexibility that they’re looking for?” asked Trodella. “Are you offering them the ability to provide their feedback, and their input, and be a part of the products or solutions that you’re building? Will you recognize them? Will they be able to have access to leadership in a way that is constructive and productive?” All are key questions that current employees will be asking their bosses in the workplace of the future, and are ones that prospective employees will ask potential employers before signing on the dotted line.

Such changes shouldn’t occur in a vacuum, however — and just because an executive in the C-suite thinks it should happen doesn’t mean it should. Before investing large amounts of money overhauling your business practices to make them more future-focused and integrating smart new technology to help open up lines of connection between the front line and the C-suite, make sure to talk to those for whom any change will be felt the most.

“Talk to your people,” said Guthkelch. “It’s as straightforward as that. Don’t try to second-guess what they want, unless you are actually doing the job yourself. Ask them what they want. Ask them what’s going to make their work better. What’s going to enable them to feel more connected to the organization, which is going to enable them to do their job most effectively.”

There will likely be a long list of complaints and concerns, and niggling issues that ought to be tackled. Developing a future-proofed workplace isn’t easy, after all. But thinking calmly and clearly about which issues to tackle — and in what order — can reap benefits. “Look at your processes, look at your technology stacks and understand where you have gaps,” advised Guthkelch. “Then from that, look at where you can make some quick wins that will be most impactful for not only you as leadership, but more specifically for your people that is going to really enable them to turn up, to work and to thrive in the role that they’re doing.”

Read the series:

Chris Stokel-Walker is a freelance technology and culture journalist and author of “YouTubers: How YouTube Shook Up TV and Created a New Generation of Stars.” His work has been published in The New York Times, The Guardian and Wired.

The Tesla CEO’s decision to turn down a seat on Twitter’s board of directors puzzled many. Restrictions on his role and a little-noticed obstacle to a Twitter takeover may have played a part.

Musk will be free to seek a bigger stake in Twitter. But overturning

Hirsh Chitkara ( @HirshChitkara) is a reporter at Protocol focused on the intersection of politics, technology and society. Before joining Protocol, he helped write a daily newsletter at Insider that covered all things Big Tech. He’s based in New York and can be reached at [email protected].

Elon Musk’s decision to turn down a seat on Twitter’s board of directors came as a surprise to most observers. Musk, a Twitter power user, has no shortage of ideas on how to change the service, and a board seat seemed like a logical perch to shape Twitter to his liking.

A deeper understanding of how companies operate and the strictures placed on board members help explain why Musk and Twitter found themselves unwinding a hastily hammered-together agreement to place him on the board. There’s also the matter of a little-noticed shareholder vote last summer which places a big obstacle in the way of anyone seeking to overhaul Twitter’s governance.

So what exactly is going on? The short answer is nobody has all the answers yet. Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal didn’t lend much clarity when he simultaneously argued Sunday that appointing Musk to Twitter’s board and moving on without him as a director were both for “the best.” Musk’s U-turn will certainly relieve some of the pressure Agrawal faced from some Twitter employees who vocally resisted the idea of taking orders from a self-labeled “free speech absolutist” whose own companies have been roiled by charges of racist and sexist harassment.

Twitter’s corporate governance helps explain how things played out and what’s likely to happen next. Musk will now be free to accumulate an ownership stake beyond 14.9% — though exercising that power to change Twitter’s board may prove difficult. And a conspicuous reference to a “background check” in Agrawal’s statement may have been more intentional than you think.

Agrawal’s dealings with Musk are far from over, and the Twitter CEO acknowledged that “Elon is our biggest shareholder and we will remain open to his input.” Musk has been uncharacteristically quiet — which is to say he hasn’t tweeted since Sunday afternoon and deleted several posts in which he proposed increasingly wild ideas for Twitter. He did, however, like a reply to Agrawal’s statement that proclaimed, “Let me break this down for you … Elon was told to play nice and not speak freely.”

What would it take for Musk to gain a controlling stake in Twitter?

Musk controls 9.1% of Twitter’s outstanding shares, likely making him the company’s second-largest shareholder behind mutual-fund giant Vanguard and the largest individual shareholder. To have a controlling stake, Musk would need to hold more than 50% of Twitter’s voting stock. So unless Musk is willing to pay a huge premium for the rest of Twitter’s shares, he’ll have to work with other shareholders if he wants to force Twitter to make specific changes.

Lone investors are seldom in a position to unilaterally demand changes, and that’s particularly true for a company the size of Twitter. Vanguard — one of the world’s largest investment funds with around $7 trillion in assets under management — held a 10.3% stake in Twitter common stock as of the end of March. Morgan Stanley held an 8.4% stake as of the end of 2021. Few individuals hold meaningful stakes: Co-founder Jack Dorsey held a little over 2% of Twitter’s shares as of its most recent proxy filing.

A stake the size of Musk’s is enough to command an audience from institutional investors, according to Santa Clara University School of Law professor Stephen Diamond, who advises activist investors in corporate governance matters, including some involved in a campaign aimed at Tesla.

Whether Musk proves persuasive in those meetings may be crucial. Investors are obviously pleased with Tesla’s huge run-up in market value, but Vanguard has clashed with Tesla over governance issues.

What’s the upside of having a board seat?

Shareholders don’t get a direct say in the management of the company. Rather, the shareholders elect board members who exercise oversight of company management. A CEO serves at the behest of the board, and it’s only in rare circumstances where the CEO has maintained power over board appointments — see Mark Zuckerberg at Meta — that that power dynamic has been reversed.

“The company must be managed by or under the direction of the board of directors — period, end of story,” Diamond told Protocol.

Board directors are insiders and in theory have access to all the same information the CEO has. By contrast, a typical investor only receives public financial disclosures. That would give Musk a theoretical advantage

So in Musk’s case, gaining a seat on Twitter’s board of directors would have been a critical first step towards shaping Twitter to his liking. Musk would have become the 12th board member at Twitter. One vote out of twelve doesn’t get you much.

What restrictions would Musk have faced as a Twitter board member?

Musk made some key concessions in his agreement to join the Twitter board. Most notably, he couldn’t increase his ownership stake beyond 14.9%. He’d also have to abide by Twitter’s code of conduct, which applies to board members as well as employees.

Board members must also uphold a fiduciary duty to their fellow shareholders. That means Musk would have to justify his vision for Twitter in terms of shareholder value. It couldn’t just be “free speech is good for society,” but rather “free speech is good for our bottom line.”

“I don’t actually think you can continue in a corporate governance role to just advocate for free speech at all costs,” said Ann Skeet, senior director at Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics.

What can he do now that he couldn’t do as a board member?

Abandoning the board seat agreement frees Musk to buy more Twitter shares, which would give him more leverage to demand changes. A larger ownership stake could allow Musk to lobby for additional seats on the board for his allies.

Shareholders didn’t pass a proposal to change Twitter’s board structure last year that would have smoothed Musk’s path. That “declassification” proposal would have allowed for annual elections of directors; currently directors are elected in classes serving three-year terms. Without it, Musk or anyone else trying to change the composition of Twitter’s board would have to wait years to replace directors. Twitter has said it would try to get shareholder approval for the proposal again this year.

Aside from winning board seats, Musk can only demand changes from Twitter by engaging in a hostile tender offer. Such campaigns are extremely rare and often prohibitively expensive, even by Musk’s standards.

What was up with Twitter asking for a background check?

Agrawal mentioned a background check in his tweet about Musk, and Twitter went further in a filing, saying his appointment was conditioned on both the background check and filling out a directors and officers questionnaire.

The D&O questionnaire asks for information required so the company can make needed SEC filings, for example. And one standard question asks about violations of federal or state securities laws. Musk settled securities fraud charges with the SEC in 2018 and is under an ongoing agreement limiting his ability to tweet about Tesla and preventing him from serving as chairman of Tesla’s board.

Both the background check and the D&O questionnaire are standard practice, according to Diamond.

“Were they signaling something by repeating that? I don’t know,” said Diamond. “It’s possible that they started to actually pay attention to Elon Musk and said, ‘Wait a minute … this guy is a bit of a loose cannon.’”

“I don’t think [Agrawal] would just slip that in without having thought about it in advance,” said Skeet. She added that Agrawal may have been signaling that “Elon Musk might be the kind of person who’s not willing to submit themselves to that kind of review — and that unwillingness to participate in the fundamental processes of being screened and selected to a board is a flag.”

Hirsh Chitkara ( @HirshChitkara) is a reporter at Protocol focused on the intersection of politics, technology and society. Before joining Protocol, he helped write a daily newsletter at Insider that covered all things Big Tech. He’s based in New York and can be reached at [email protected].

The Asian nation’s payments network blocked rupee-to-crypto transactions — a setback for Coinbase’s global ambitions.

Brian Armstrong, CEO of Coinbase, speaks at the company’s event in Bengaluru, India.

Benjamin Pimentel ( @benpimentel) covers crypto and fintech from San Francisco. He has reported on many of the biggest tech stories over the past 20 years for the San Francisco Chronicle, Dow Jones MarketWatch and Business Insider, from the dot-com crash, the rise of cloud computing, social networking and AI to the impact of the Great Recession and the COVID crisis on Silicon Valley and beyond. He can be reached at [email protected] or via Google Voice at (925) 307-9342.

Days after Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong declared that “India is a magical place,” the crypto powerhouse found out that the country can also be a tricky place to do business.

Coinbase suspended rupee-to-crypto transactions through India’s Unified Payments Interface just days post-launch, after the country’s real-time payments network essentially said the company wasn’t authorized to use it.

“We are not aware of any crypto exchange using UPI,” India’s National Payments Corporation, which operates the network, said in a tweet last week.

Coinbase said it was “committed to working” with the umbrella organization for retail payments and settlements in India “to ensure we are aligned with local expectations and industry norms,” a company spokesperson said. The company’s website now says only crypto-to-crypto transactions are offered in India.

It was a stunning fumble for the crypto company which has vowed to “scale globally.” Coinbase has been aggressively expanding in India. Its India tech hub, which launched last year, has more than 300 employees and the company said it expects to hire over 1,000 more this year.

Armstrong said its venture arm, Coinbase Ventures, has invested $150 million in Indian tech companies focused on crypto and Web3.

“India has built a robust identity and digital payments infrastructure and implemented it at rapid scale and speed,” Armstrong said in a blog post. “I believe crypto has a big future here. We’re excited to help build that future.”

But the Coinbase setback in India underlined the challenges faced by crypto companies looking to expand their reach globally, given the “different levels of maturity and perspectives around digital assets from country to country,” Logan Allin, managing partner of Fin Venture Capital, said.

Fintech companies have faced criticism for expanding to new jurisdictions without making sure that they are complying with regulations.

“Digital asset exchanges like Coinbase have continued to take the approach of asking for forgiveness versus permission, which is not a sustainable model for global scale,” Allin told Protocol.

In many cases, crypto companies find themselves dealing with countries that “have taken a cautious and conservative tone with very little prescription and regulatory clarity, which is causing further confusion and foot faults at the company level.”

One issue Coinbase may be facing is the time it takes to recruit local teams. The company has 22 openings in international operations, including several country heads and regional managing directors.

Benjamin Pimentel ( @benpimentel) covers crypto and fintech from San Francisco. He has reported on many of the biggest tech stories over the past 20 years for the San Francisco Chronicle, Dow Jones MarketWatch and Business Insider, from the dot-com crash, the rise of cloud computing, social networking and AI to the impact of the Great Recession and the COVID crisis on Silicon Valley and beyond. He can be reached at [email protected] or via Google Voice at (925) 307-9342.

Netflix designers thought they had the perfect icon for a new feature. Then the service’s subscribers started chiming in.

Janko Roettgers (@jank0) is a senior reporter at Protocol, reporting on the shifting power dynamics between tech, media, and entertainment, including the impact of new technologies. Previously, Janko was Variety’s first-ever technology writer in San Francisco, where he covered big tech and emerging technologies. He has reported for Gigaom, Frankfurter Rundschau, Berliner Zeitung, and ORF, among others. He has written three books on consumer cord-cutting and online music and co-edited an anthology on internet subcultures. He lives with his family in Oakland.

For nearly five years, Netflix has had simple thumbs-up and thumbs-down icons to express viewing preferences and help its algorithms provide better recommendations. However, in surveys, people frequently expressed that this binary type of voting didn’t really do their taste justice.

What if they were really, truly in love with a show?

Tasked to come up with a better way to express such levels of adoration, the streaming service recently explored the idea of adding a heart icon to the Netflix app. The heart seemed like an obvious choice. It’s a universal sign of love, and widely used in apps like Instagram and Twitter.

But Netflix wouldn’t be Netflix if the company didn’t put features like these through some rigorous testing; in this case, it took nearly a year. During that time, the company discovered that hearts were actually not the best-performing feature after all, and instead settled on a new two-thumbs-up option that is being made available to its subscribers worldwide this week.

Here’s how that change of heart came about.

Netflix rolled out its new two-thumbs-up feature across its mobile and smart TV apps as well as its website Monday. Subscribers are being advised that this type of feedback directly affects future recommendations. A thumbs-down means that a title won’t get suggested again; a thumbs-up will result in Netflix recommending similar content. Two thumbs up means that “we know you’re a true fan,” as the Netflix mobile app puts it.

The company kicked off its work on the feature about a year and a half ago based on feedback it was getting in surveys and research interviews from its subscribers. “We were hearing from members that ‘like’ and ‘dislike’ was not sufficient,” said Christine Doig-Cardet, who leads the company’s personalized UI product innovation team. “There were some shows that they really, really, really enjoyed. Differentiating between what they love and what they like was important.”

Once the decision was made to solve this problem, Netflix kicked off a series of design sprints to come up with visuals for this level of fandom. Some of the early ideas included the heart, an applause icon, shooting stars and others. Designers also consulted with the company’s globalization team to find an icon that was truly universal. “The design team and the globalization team really [homed] in on the symbols that connote love,” said Netflix director of Product Design Ratna Desai. “We wanted it to be very precise, very concise, because we wanted this to be a very quick interaction.”

At the same time, Netflix continued to query its subscribers, who had a different suggestion. “We had a lot of interviews and surveys, [and] the heart was not really resonating,” Doig-Cardet said. “The idea that came from members was: Why don’t you just try two thumbs up?”

At that point, two front-runners emerged. The heart seemed like an obvious choice, but two thumbs up also seemed to work well with Netflix’s existing iconography. Plus, as anyone who has ever read a review by the late Roger Ebert knows, it has long signified a vote of confidence for great entertainment.

Going with what its subscribers wanted seemed like a good idea, giving credence to the two thumbs up. But what if those subscribers were wrong?

“Some people can speak loudly,” Doig-Cardet said. “But when you look at the whole picture, talk to a lot of different members and see how they engage with the different features, it doesn’t actually always [match] the initial loud voices.”

Netflix has long tried to figure out how to best collect member-based content ratings, and dealing with those loud voices has been challenging. In its early days, Netflix used to offer a five-star ratings system, similar to the way people rate their Uber drivers.

At the time, Netflix displayed an average of those ratings on its website to convey how well-liked a title was among subscribers. This resulted in some titles having 4.5 stars, or other fractions, leading people to wonder why they couldn’t rate in half-star increments as well.

Thousands of people told the company in surveys that they wanted this level of granularity, but Netflix employees weren’t sure whether those opinions reflected how people actually used the service. To make sure it wasn’t falling for the opinions of a vocal minority, Netflix resorted to something that has become a key part of its product development tool chest over the years: an A/B test.

In the case of the half-star test, the results were obvious: Ratings dropped significantly when people were asked to provide feedback with that level of granularity. In other words: A/B testing proved the loudest voices wrong.

Netflix repeated this kind of testing when it completely replaced the five-star ratings with thumbs in 2017. In A/B tests ahead of that change, the company saw ratings activity increase by 200% with thumbs-up and thumbs-down icons. Part of the issue was that these icons were just simpler, but a closer look at the data also revealed that they tended to be more accurate: People would aspirationally rate titles five stars that they deemed worthy of that status, including award-winning documentaries that would then linger unwatched in their queues for months. At the same time, they would frequently binge on reality TV shows that they themselves had rated just three stars.

Now, Netflix is ready to again add a bit more complexity to those ratings. That’s in part because media consumption habits and app interfaces have changed across the board. “People are using Netflix in the context of their overall lives,” Desai said. “They are interacting with Instagram, with various social networks, with ride-share apps.” Some of the interaction patterns of those apps and experiences weren’t easily applicable to Netflix, which is primarily used on TVs and has a much bigger focus on leanback entertainment than, for instance, Instagram. “But there are a few levers that our members are now asking for that they didn’t in the past,” she said.

Still, there were some unresolved questions, including what would perform better: Hearts or thumbs? And would either actually have a lasting impact beyond addressing those loud voices in surveys and other forms of qualitative research?

“We have been in situations where we may hear very strong points of view in a qualitative setting that go against what we find out in A/B testing,” Desai said. ”That’s when the fun begins.”

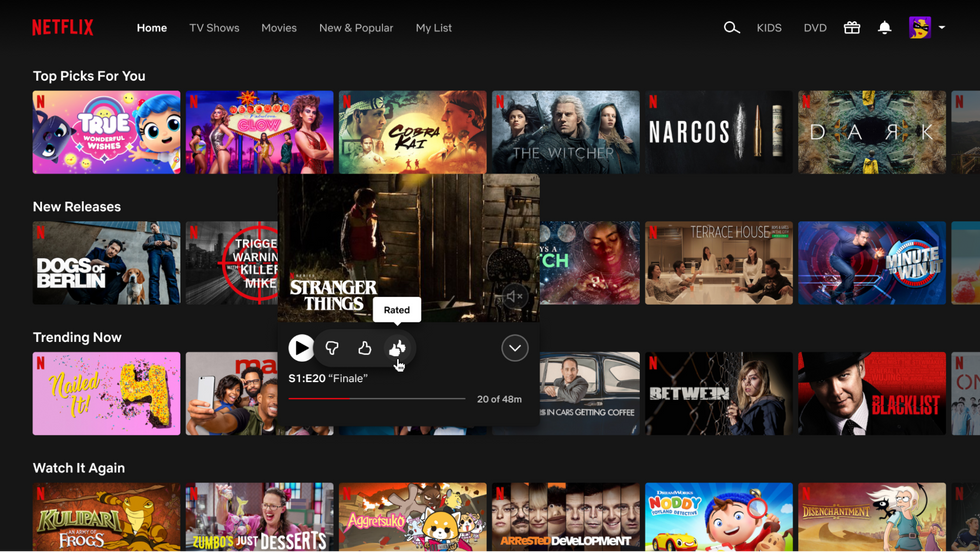

Netflix began a series of A/B tests for the new ratings feature last summer.Image: Netflix.

Netflix began a series of A/B tests for the new ratings feature last summer.Image: Netflix.

Netflix began a series of A/B tests for the new ratings feature last summer, trialing both the heart and the two-thumbs-up option. At the same time, the company continued to query subscribers, including those enrolled in the tests, to see whether the new features were actually providing value.

Testing of the feature extended into the fall, as the teams working on it wanted to make sure they got things right. “We don’t rush a test,” Doig-Cardet said. “Sometimes, there’s this impetus to just launch early and break things and all of that. That’s not [our] approach.” One reason for conducting A/B tests over weeks or even months is to let people get used to a feature and see whether engagement stays high, or whether people are attracted to the novelty of a feature, and then get bored with it.

In the end, the numbers were clear: Providing additional feedback worked. “We saw a very big lift in engagement because people had a new way to talk to us,” Desai said. That lift was a lot bigger with the two thumbs up than with the heart, which was a surprise, as people within Netflix had expected the heart to win.

Those kinds of unexpected outcomes are what make A/B testing so valuable, Doig-Cardet said. “If we weren’t surprised, we would be doing something wrong,” she said. “We would be validating our own assumptions, rather than letting numbers direct what is a better experience.”

Netflix’s extensive use of A/B testing has been well-documented over the years, including by its own data science team. The company is constantly testing a number of different features with subsets of its audience. Basically, if you’re a Netflix subscriber, there’s a decent chance that you are enrolled in some kind of test right now.

Some of these tests are for obvious interface tweaks, and some are related to under-the-hood codec or infrastructure changes. In fact, Netflix does so many tests that members can be enrolled in more than one test at the same time, which is why the company developed an entire experimentation platform that helps its data science team avoid testing conflicts and make sense of all the collected data. (Netflix does offer members a chance to opt out of tests through their account settings.)

However, the development of the new two-thumbs-up feature also shows that A/B testing alone isn’t enough. Without also talking directly to subscribers, the company would have prioritized the development of the heart icon and wouldn’t have given two thumbs up a chance to prove itself in A/B tests. “We take this multipronged approach of looking at a lot of different inputs,” Doig-Cardet said. “We’re capturing insights from our customer service, from surveys, from interviews that we’re doing, and using all of that to inform [what] we should be investing in and testing.”

Both surveys and A/B tests do come with a risk of exposing future features to the public eye. Subscribers frequently post about new things they spotted in the app, and reporters tend to jump on those stories to shine a light on the company’s roadmap. For Netflix, that’s just a cost of doing business. “We’re comfortable making that trade-off of providing early visibility because we want to make sure that it’s working for our members,” Doig-Cardet said.

“In previous places I worked, there’s this amazing unveiling of the feature, with the campaign and all of that,” Desai added. Netflix instead operates a bit more in the open, which includes testing new and unannounced features with tens of thousands of members.

“This is our bread and butter,” Desai said. “It’s our secret sauce to how we innovate.”

Janko Roettgers (@jank0) is a senior reporter at Protocol, reporting on the shifting power dynamics between tech, media, and entertainment, including the impact of new technologies. Previously, Janko was Variety’s first-ever technology writer in San Francisco, where he covered big tech and emerging technologies. He has reported for Gigaom, Frankfurter Rundschau, Berliner Zeitung, and ORF, among others. He has written three books on consumer cord-cutting and online music and co-edited an anthology on internet subcultures. He lives with his family in Oakland.

To give you the best possible experience, this site uses cookies. If you continue browsing. you accept our use of cookies. You can review our privacy policy to find out more about the cookies we use.