Hi, what are you looking for?

Recent revelations from an alleged music industry insider paint a disturbing picture.

By

Published

Flipboard

Reddit

Pinterest

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Email

The fake artist problem on streaming platforms is far more ominous than it seems at first glance. You might think this can’t be much different than a cover band, no? Or, at worst, maybe it’s just another form of music piracy, which has been happening for ages.

In fact, the problem is much worse than these.

The streaming model allows for abuses beyond anything a pirate ever envisioned. Algorithms now determine how a huge portion of song royalties are allocated, and if you can manipulate the algorithms you can send enormous sums of money into your bank account.

The root of the problem is the increasingly passive nature of music consumption. People will often ask Alexa, or some other digital assistant, to find background music for a specific task—studying, workout, housework, relaxation, etc. Or they will rely on a pre-curated playlist for that purpose. They don’t pay close attention to the artists or song titles, and this is what creates an opportunity for abuse.

This kind of scam wasn’t possible before streaming. People obviously listened to music while studying or working, but they either picked out the record themselves, or relied on a radio station to make the choice. Radio stations were sometimes guilty of taking payola, but even in those instances a human being could be held accountable. But with AI now making the decisions, everything can be hidden away in the code.

The size of this market is much larger than people realize. For example, a search for ‘jazz’ on a streaming platform leads you to a large number of playlists. Here’s the first one I got on Spotify.

And what artists do you hear if you click on this? Maybe Louis Armstrong or John Coltrane? Perhaps something more introspective, like Bill Evans or Ahmad Jamal or mid-period Miles Davis? Maybe some appealing vocals by Ella Fitzgerald or Billie Holiday?

- Related article: Best Jazz Albums of 2021

In fact, I only recognized two names in the first 15 tracks. Here are a few of the curated tracks:

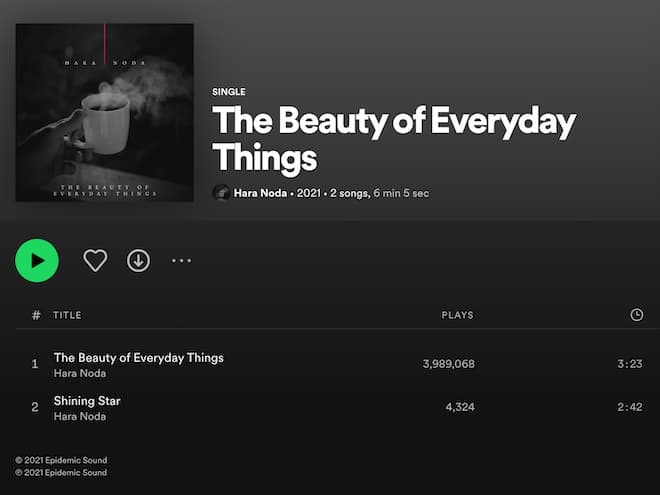

Who exactly plays in the Tribute Trio? I can’t answer that question. Who is Hara Noda? I didn’t know until I did a Google search (more on that below), but it wasn’t reassuring that the album has only two tracks, and features a coffee cup on the cover.

Note that one of the Hara Noda tracks has almost four million plays—that’s more streams than are attributed to most of the tracks on Jon Batiste’s We Are, which just won the Grammy for Album of the Year.

That’s an amazing fact to consider.

Can you really reach a larger audience by getting on a background jazz playlist than taking home the most coveted Grammy? I hate to share the bad news, my friends, but the world has changed.

Meanwhile, the other track from Hara Noda has only four thousand streams. Clearly placement on a featured playlist has generated a load of royalties. But for whom?

Hara Noda seems to be a real person, working as a producer and drummer in Sweden—which, by pure coincidence, is the same place where Spotify has its headquarters. In fact, the number of fake artists whose music comes out of Sweden is extraordinary. But even the numbers may be misleading. According to one survey, “about 20 people are behind over 500 artist names.”

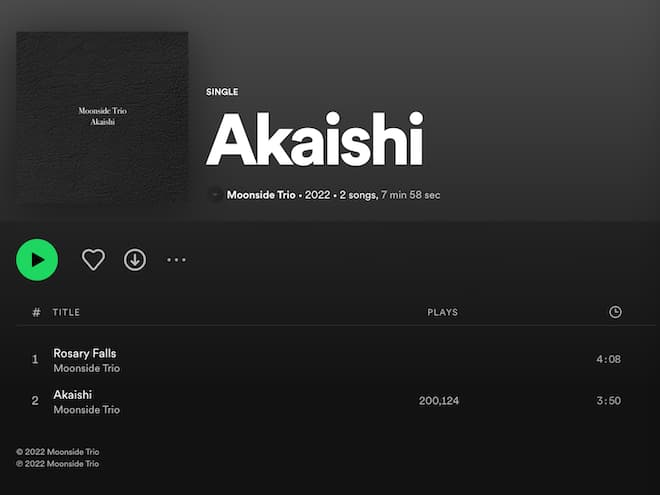

The Moonside Trio, also on the Spotify jazz playlist, provides even less info—they have a totally black album cover, with (again) just two tracks. One of the tracks has 200,000 plays and the other one apparently no plays. Hmmmm.

But somehow these artists beat out every musician in the jazz hall of fame.

What’s going on here?

I’ve found the media coverage of this issue is very disappointing. But, fortunately, an insider recently shared some disturbing details with a music blog. These are more revealing than anything you will read in the major music trade journals.

I can’t attest for the accuracy of these statements, and I don’t know the original source. I merely pass them on because I found them helpful in my attempts to understand the situation.

Here are six key passages:

1. “Across all streaming services an increasing share of consumption is happening in areas of the product that is entirely controlled by the DSP [digital streaming platform], because as it turns out, most users prefer easy access to pre-curated experiences vs doing the work of actively finding what to listen to.”

2. “Even Sony and Universal Music created playlists for these types of use cases under their Digster and Filtr brands long before Spotify ever did.”

3. “Interestingly, all of these ‘artists’ are all discovered on Sony-controlled playlists with very generic search-optimized titles, and millions of followers if you add all the small niche playlists together.”

4. “While majors are invested in this space, there are many extremely profitable and more successful independent companies doing the same.”

5. “The songwriters and producers of these tracks are either paid a fixed fee per track or a combination of a low advance and reduced royalty rate and it works because these ‘labels’ can guarantee millions of streams through their own network of search engine optimized DSP playlists and YouTube channels.”

6. “Make no mistake, all DSPs are engaging in the above. Spotify is taking more heat because they are the largest and most transparent, whereas Apple, Amazon, Deezer and Tencent makes it much more difficult for journalists like yourself to see what is happening since there are no stream counts, writer or even label credits.”

1. “Across all streaming services an increasing share of consumption is happening in areas of the product that is entirely controlled by the DSP [digital streaming platform], because as it turns out, most users prefer easy access to pre-curated experiences vs doing the work of actively finding what to listen to.”

2. “Even Sony and Universal Music created playlists for these types of use cases under their Digster and Filtr brands long before Spotify ever did.”

3. “Interestingly, all of these ‘artists’ are all discovered on Sony-controlled playlists with very generic search-optimized titles, and millions of followers if you add all the small niche playlists together.”

4. “While majors are invested in this space, there are many extremely profitable and more successful independent companies doing the same.”

5. “The songwriters and producers of these tracks are either paid a fixed fee per track or a combination of a low advance and reduced royalty rate and it works because these ‘labels’ can guarantee millions of streams through their own network of search engine optimized DSP playlists and YouTube channels.”

6. “Make no mistake, all DSPs are engaging in the above. Spotify is taking more heat because they are the largest and most transparent, whereas Apple, Amazon, Deezer and Tencent makes it much more difficult for journalists like yourself to see what is happening since there are no stream counts, writer or even label credits.”

It’s worth reading the whole article. Although, as noted above, I can’t verify these claim, the charges deserve close attention. They suggest that a huge systemic and structural shift in industry payouts is happening—one that has tremendous impact on the livelihoods of working musicians.

In the future, I plan to write an article on the history of fake artists—which is an interesting subject in its own right. And it’s much more amusing than the topic at hand, which is no laughing matter. But none of those predecessors could have dreamed of anything on the scale of what’s happening now.

Even the term fake artists doesn’t really do justice to the scope of the situation—because, as we have seen, it’s not the musicians, real or otherwise, who are at the root of the situation, but the dominant players in the industry.

That roster includes some of the largest corporations in the history of the world. Is anyone big enough to take them on? I seriously doubt it.

Ted Gioia is a leading music writer, and author of eleven books including The History of Jazz and Music: A Subversive History. This article originally appeared on his Substack column and newsletter The Honest Broker.

Home > Latest > Articles > Music > The Fake Artists Problem Is Much Worse Than You Realize: The Honest Broker

Richard Townsend

April 14, 2022 at 12:24 pm

Hmm, while I accept that there are fake artists, you’ve not presented any evidence that any of the artists you’ve shown or mentioned are fake.

Many labels run very popular playlists for their artists, and in some cases, joining a label to get these plays can be a sensible idea for real artists.

Likewise lots of real artists pitch to Spotify playlists as these can generate millions of plays. Nothing wrong with that at all. If these get more plays than a Grammy winning artist, then that’s fine as far as I’m concerned.

Tim

April 14, 2022 at 4:06 pm

Fascinating and infuriating. I actually worked for a fake-artist label back in the 90s, which turned out to be a way to scam investors. I didn’t know the scam until the sheriff padlocked the door. Very important story to get to the public. Thank you.

rl1856

April 14, 2022 at 5:39 pm

Think about how the money is distributed when a title is included in a suggested playlist. Someone has to be paid…it could be Miles/Coltrane/Ella at a premium rate, or an unknown artist paid a much lower rate. I think “fake artist” may not be the correct term in this case. Perhaps, invisible, or contracted may be more accurate. In essence an unknown musician or group is engaged by a music content company, then paid a flat fee and/or a low royalty rate to produce music. The content company ensures that the commissioned product receives the most exposure, to either save (high) fees paid to other artists, or to ensure a higher % of a set fee is paid to the content company. The house always wins. As for me, I am not a fan of someone else selecting what I listen to. OTOH the apathy of the general public makes this trend profitable.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Flipboard

Reddit

Pinterest

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Email

The future of the music industry may be in jeopardy if more than few of these predictions come true. Let’s hope I’m wrong.

Has old music killed new music? Orville Peck and Adia Victoria deliver two gems in a week filled with some mediocre releases.

Emiko aka @thathifigirl takes a hard look at how much musicians earn when their songs are streamed.

All the growth in the music business now comes from old songs — how did we get here, and is there a way back?

Interest in jazz kissa is growing internationally, and kissa-inspired listening venues are appearing outside Japan; can they compete with the real thing?

This episode explores why vintage audio hi-fi gear has suddenly become so sought after with @audioloveyyc and @budget_audiophiler.

Why did Bandcamp allow one of the biggest gaming companies in the world to acquire it? We think it’s rather obvious.

How did I get here? How the New Wave music movement changed everything and all of us. And we’re not speaking in tongues.

ecoustics is a hi-fi and music magazine offering product reviews, podcasts, news and advice for aspiring audiophiles, home theater enthusiasts and headphone hipsters. Read more →

Copyright © 1999-2022 ecoustics | Disclaimer: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site.